Ancient Roman Way unearthed at the Tarsus civic center.

Paul of Tarsus, also known as Saul, Paulus, and Saint Paul the Apostle (AD 3–14 — 62–69), is widely considered to be central to the early development and spread of Christianity, particularly westward from Jerusalem. Many Christians view him as an important interpreter of the teachings of Jesus.

Paul is described in the New Testament as a Hellenized Jew and Roman citizen from Tarsus in present-day Turkey. He was a persistent persecutor of Early Christians, almost all of whom were Jewish or Jewish proselytes, until his experience on the Road to Damascus which brought about his conversion to faith in Jesus Christ. After his baptism, Paul sojourned in Arabia (probably Nabataea) until joining the early Christian community in Jerusalem and staying with St. Peter for fifteen days (Gal 1:13–18). Through his epistles to Gentile Christian communities, Paul articulated his position on the relationship between Jewish Christians and Gentile Christians, and between Mosaic Law and the teachings of Jesus.

Paul is venerated as a Saint by various groups, including the Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, and Anglican traditions, and by some Lutherans. He is the patron saint of Malta and the City of London, and has also had several cities named in his honor (including São Paulo, Brazil, and Saint Paul, Minnesota). He is venerated as a prophet by Mormons.

Paul's epistles form a fundamental section of the New Testament, and his efforts to advance Christianity among the Gentiles, for which he is considered to be a significant source of early Church doctrine, have been subject to various interpretations. Traditional Christianity includes the Pauline Epistles as part of the New Testament Canon, and asserts that Paul's teachings are in complete harmony with the teachings of Jesus, such as the Sermon on the Mount, and the apostles.

Life

In reconstructing the events of Paul's life, there exist two primary sources: Paul's own surviving letters, and the narrative of Acts of the Apostles, which at several points draws from an eyewitness source (the so-called "we passages"). Problems with these sources include the following: Paul's surviving letters were written during a short period of his life (perhaps only between 50 and 58), and the authenticity of some is questioned, and certain parts of Acts have drawn suspicion (e.g., Paul's presence at the death of Stephen [7:58; 8:1' 22:20]). The apocryphal Acts of Paul and Thecla is usually dismissed by scholars as a 2nd century novel because it includes events that do not coincide with any of those recorded in either Acts or Paul's letters.

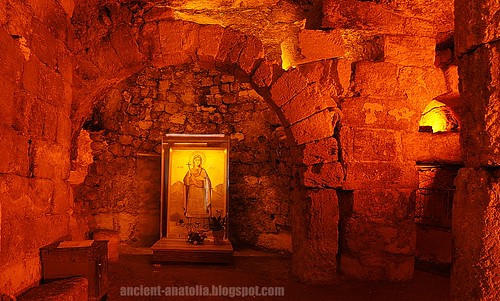

Saint Thecla Ancient Cave Chapel at Seleucia ad Calycadnum, Silifke today.

Raymond E. Brown summarized three approaches used by historians when using the sources: The traditional approach is to completely trust the narrative of Acts, and fit the materials from Paul's letters into that narrative. The approach used by a number of modern scholars is to distrust Acts, sometimes entirely, and to use the material from Paul's letters almost exclusively. An intermediate approach treats Paul's testimony as primary, and supplements this evidence with material from Acts.

The following construction of a possible chronology is based largely on this third approach.

Early life

Paul described himself as an Israelite of the tribe of Benjamin, circumcised on the eighth day, a Pharisee (Rom 11:1; Phil 3:5), and of the "Jews' religion . . . more exceedingly zealous of the traditions" (Gal 1:14 KJV). He was born as Saul in Tarsus of Cilicia and received a Jewish education. Acts records that Paul was a Roman citizen—a privilege he used a number of times in his defence, appealing convictions in Judea to Rome (Acts 22:25 and 27–29).

The issue of Roman citizenship has given rise to various views. The reference to Paul's Roman citizenship inherited from his father derives from Acts 22:26–28 and 16:37. Some scholars have expressed skepticism over this rare privilege since Paul did not mention it in his surviving writings. On the other hand, the Ebionites and some Restorationists have argued that Paul was a Roman who tried successfully to convert to Judaism so he could take a Jewish bride. They state that citizenship would have required participation in the Imperial Cult, which would have been in conflict with Hebrew religious ideals.

The common assumption is that Paul was never married. Paul himself confirmed this writing: "Now to the unmarried and the widows I say: It is good for them to stay unmarried, as I am" (1 Cor 7:8). No historical source mentions Paul having a wife. However, some argue that the social norm of the time required Pharisees and members of the Sanhedrin to be married. If Paul were a Pharisee, and some think even a member of the Sanhedrin, he might have been married at one point.

According to Acts 22:3, Paul studied in Jerusalem under the Rabbi Gamaliel, well known in Paul's time. Thomas Robinson depicts Paul as coming to study in Jerusalem under Gamaliel, when Shammai became Nasi of the Sanhedrin, and during the rise to supremacy of the house of Shammai from 20. However, some scholars, such as Helmut Koester, have expressed doubts that Paul either was in Jerusalem at this time or studied under this famous rabbi. Paul supported himself during his travels and while preaching—a fact he alludes to a number of times (e.g., 1 Cor 9:13–15); according to Acts 18:3, he worked as a tentmaker. According to Romans 16:2, he had a patroness (Koine Greek προστάτις prostatis) named Phoebe.

Some have speculated that Paul suffered from Ophthalmia neonatorum, a disease common in the East which causes painful eye weakness and partial blindness. They cite his frequent use of an amanuensis, his comments in the Epistle to the Galatians on how large his own handwriting was (Gal 6:11), and his compliments of the Galatians' charity: "I can testify that, if you could have done so, you would have torn out your eyes and given them to me" (Gal 4:15). Eusebius in his Church History (Book VI) chapter 25 noted that Origen claimed that "Paul . . . did not write to all the churches which he had instructed and to those to which he wrote he sent but few lines." Further possible allusions include his self-description as unimpressive in person (2 Cor 10:10), and, more speculatively, his remarks about a "thorn in the flesh" (2 Cor 12:7–10).

Some think that Paul had at least one brother, Rufus, on a literal rather than a figurative reading of Romans 16:13.

Conversion and early teachings

Paul himself admits that he at first persecuted Christians to the death (Phil 3:6), and Acts places him at the martyrdom of Stephen (Acts 7:58–60; 22:20), but Paul later embraced Christianity (c.35 AD):

"Meanwhile, Saul was still breathing out murderous threats against the Lord's disciples. He went to the high priest and asked him for letters to the synagogues in Damascus, so that if he found any there who belonged to the Way, whether men or women, he might take them as prisoners to Jerusalem. As he neared Damascus on his journey, suddenly a light from heaven flashed around him. He fell to the ground and heard a voice say to him, "Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me?" "Who are you, Lord?" Saul asked. "I am Jesus, whom you are persecuting," he replied. "Now get up and go into the city, and you will be told what you must do." The men traveling with Saul stood there speechless; they heard the sound but did not see anyone. Saul got up from the ground, but when he opened his eyes he could see nothing. So they led him by the hand into Damascus. For three days he was blind, and did not eat or drink anything" (Acts 9:1–9; c.f. Paul's explanation to King Agrippa, Acts 26, and Galatians 1:13–16).

Following his stay in Damascus after conversion, Paul first went to live in the Nabataean kingdom (which he called "Arabia"), then came back to Damascus, which by this time was under Nabatean rule. Three years after his conversion (the exact distribution of this between Arabia and Damascus is disputed), he was forced to flee from that city, via the Bab Kisan / The Kisan Gate (Gal 1:17, 20), under the cover of night (Acts 9:23, 25; 2 Cor 11:32ff.) because of the reaction to his preaching by some of the strict Jewish authorities. Later Paul traveled to Jerusalem, where he met James the Just and Saint Peter, staying with the latter for fifteen days (Gal 1:13–18).

Following this visit to Jerusalem, Acts records that Paul went to Antioch, whence he set out to travel through Cyprus and southern Asia Minor to preach of Christ—a labor that has come to be known as his "First Missionary Journey" (Acts 13:1–14:28). In Derbe he and Barnabas were called "gods . . . in human form" {14:11). Paul's own letters only mention that he preached in Syria and Cilicia (Gal 1:18–20). Acts records that Paul later "went through Syria and Cilicia, strengthening the churches" (15:41), but is not explicit concerning who or when the churches were founded.

For these missionary journeys, often seen as defining activities of Paul, he usually chose one or more companions for his travels, including Barnabas, Silas, Titus, Timothy, John, surnamed Mark, Aquila, Priscilla, and his personal physician Luke. He endured various hardships on these journeys, including imprisonment in Philippi, lashings and stonings, and an attempted murder (2 Cor 11:24–27). Some have speculated, based on this and 2 Corinthians 12:2–5, that Paul died as a result of stoning but was miraculously raised to life.

Consultations with the other Apostles

About 49, after fourteen years of preaching, Paul traveled to Jerusalem with Barnabas and Titus and met with the leaders of the Jerusalem church, namely James the Just, St Peter, and John the Apostle; an event commonly known as the Council of Jerusalem. This event, and its subsequent decision regarding Christianity's use of the Mosaic Law, has been the subject of much interest and many interpretations.

Acts states that Paul was part of a delegation from the Church of Antioch that went up to Jerusalem to discuss whether gentile converts needed to be circumcised (15:2). The Western text-type of 15:2 states: "For Paul spoke maintaining firmly that they should stay as they were when converted; but those who had come from Jerusalem ordered them, Paul and Barnabas and certain others, to go up to Jerusalem to the apostles and elders that they might be judged before them about this question." This question had ramifications concerning observation of the Mosaic Law in general, a matter partially addressed already by Peter in his decision concerning dietary laws and gentile Christians (11:2–9). Paul states that he had attended "in response to a revelation and to lay before them the gospel that I preach among the gentiles" (Gal 2:2). At the council, Peter said: "[God] put no difference between us and them, purifying their hearts by faith" (Acts 15:9), echoing an earlier statement: "Of a truth I perceive that God is no respecter of persons" (Acts 10:34). James issued the Apostolic Decree: "We should not trouble those of the Gentiles who are turning to God" (15:19–21), and a letter was sent back with Paul enjoining them from food sacrificed to idols, from blood, from the meat of strangled animals, and from sexual immorality (Acts 15:29).

Despite the agreement they achieved at the Council as understood by Paul, Paul recounts how he later publicly confronted Peter (accusing him of Judaizing) over his reluctance to share a meal with gentile Christians in the "Incident of Antioch". Paul later wrote: "I opposed [Peter] to his face, because he was clearly in the wrong" and said to the apostle: "You are a Jew, yet you live like a Gentile and not like a Jew. How is it, then, that you force Gentiles to follow Jewish customs?" (Gal 2:11–14). Paul also mentioned that even Barnabas sided with Peter. Acts does not record this event, saying only that "some time later", Paul decided to leave Antioch (usually considered the beginning of his "Second Missionary Journey" (Acts 15:36–18:22)) with the object of visiting the believers in the towns where he and Barnabas had preached earlier. However, contention between Paul and Barnabas over whether they should take John Mark (Barnabas' cousin) with them, and thereupon they went on separate journeys (Acts 15:36–41) — Barnabas with John Mark, and Paul with Silas. Evidence of later reconciliation includes Paul mentioning that John Mark was in prison with him, telling the church in Colossae to welcome him if he comes to them (Col 4:10).

Some scholars, such as Michael L White, have argued that the "Incident of Antioch" was more disastrous, as opposed to the description in Acts. White wrote:

Paul persuaded no one, not even Barnabas, who, according to later legends, became a protégé of Peter (cf. Acts 12:12–17; 15:36–41) . . .The blowup with Peter was a total failure of political bravado, and Paul soon left Antioch as persona non grata, never again to return... For Paul the immediate result was clear. He had to leave Antioch. He chose to embark on a new mission where there was not such a strong and traditional Jewish community.

This interpretation stands in contrast with the Catholic Encyclopedia's view that Paul's relating of the incident "leaves no room for doubt that Peter was persuaded by his arguments".

Founding of churches

Paul spent the next few years traveling through western Asia Minor, this time entering Macedonia, and founded his first Christian church in Philippi, where he encountered harassment. Paul himself described his experience: "We suffered and were shamefully treated" (1 Thess 2:2); Acts, perhaps drawing from an eyewitness (this passage follows closely on one of the "we passages"), adds here that Paul exorcised a spirit from a female slave, ending her ability to tell fortunes and reducing her value—an act the slave's owner claimed was "theft"; wherefore he had Paul briefly sent to prison (Acts 16:22). Paul then traveled along the Via Egnatia to Thessalonica, where he stayed for some time before departing for Greece. First he came to Athens where he gave his legendary speech in the Areopagus, in which he made known to them the "Unknown God" whom they already worshipped (Acts 17:16–34). Thereafter he traveled to Corinth, where he settled for three years and wrote First Thessalonians, likely the earliest of his surviving letters.

Again he ran into legal trouble in Corinth (Acts 18:12–16): "the Jews united" and complained that he was "persuading the people to worship God in ways contrary to the law." He was brought before the proconsul Gallio, who decided that it was a minor matter not worth his attention and dismissed the charges. From an inscription in Delphi that mentions Gallio, the year of the hearing is known to be 52, which aids in reconstructing an accurate chronology of Paul's life.

Following this hearing, Paul continued his preaching, usually called his "Third Missionary Journey" (18:23–21:26), traveling again through Asia Minor and Macedonia, to Antioch and back. He caused a great uproar in the theatre in Ephesus, where local silversmiths feared loss of income due to Paul's activities. Their income relied on the sale of silver statues (i.e., idols) of the goddess Artemis, whom they worshipped; and the resulting mob almost killed him (Acts 19:21–41) and his companions. Later, as Paul was passing near Ephesus on his way to Jerusalem, Paul chose not to stop, since he was in haste to reach Jerusalem by Pentecost. The church here, however, was so highly regarded by Paul that he called the elders to Miletus to meet with him (Acts 20:16–38).

Arrest, Rome, and later life

Upon Paul's arrival in Jerusalem, Paul was confronted with the rumor of teaching Antinomianism (21:21). To prove that he was "living in obedience to the law", Paul took a Nazirite vow along with some others (21:26). After the seven days of the vow, Paul was recognized outside the Jewish Temple and was nearly beaten to death by a "mob", "shouting, 'Men of Israel, help us! This is the man who teaches all men everywhere against our people and our law and this place. And besides, he has brought Greeks into the temple area and defiled this holy place'" (21:28). In 22 Paul addressed the "mob" in their language, probably Aramaic. However, the "mob" was not pleased, shouting, "Rid the earth of him! He's not fit to live!" (22:22), and after Paul's rescue by the Roman guard, he was accused of being a revolutionary, "ringleader of the sect of the Nazarenes", teaching resurrection of the dead, and thus imprisoned in Caesarea (23–26). Paul claimed his right as a Roman citizen to be tried in Rome; but owing to the inaction of the governor Antonius Felix, Paul languished in confinement at Caesarea for two years until a new governor, Porcius Festus, took office, held a hearing, and sent Paul by sea to Rome, where he spent another two years in detention (28:30).

Paul's trip to Rome, imprisonment and death

Acts describes Paul's journey from Caesarea to Rome in some detail. The centurion Julius had shipped Paul and his fellow prisoners aboard a merchant vessel, whereon Luke and Aristarchus were able to take passage. As the season was advanced, the voyage was slow and difficult. They skirted the coasts of Syria, Cilicia, and Pamphylia. At Myra in Lycia, the prisoners were transferred to an Alexandrian vessel transporting wheat bound for Italy. A place in Crete called Goodhavens was reached with great difficulty and Paul advised that they should winter there. His advice was not followed, and the vessel, driven by the tempest, drifted aimlessly for fourteen days and finally wrecked on the coast of Malta. The three months when navigation was considered most dangerous were spent there, where Paul healed the father of the Roman Governor Publius from fever and other people who were sick. He also preached the gospel and placed Publius head of this church. There he was called a god (28:6). With the first days of spring, all haste was made to resume the voyage.

Acts only recounts Paul's life until he arrived in Rome, around 61, closing with a dramatic final speech of Paul to a group of Jews who derided his teachings. Quoting Isaiah, Paul declared:

Hearing you will hear, and shall not understand; And seeing you will see, and not perceive; For the hearts of this people have grown dull. Their ears are hard of hearing, And their eyes they have closed, Lest they should see with their eyes and hear with their ears, Lest they should understand with their hearts and turn, so that I should heal them. Therefore let it be known to you that the salvation of God has been sent to the Gentiles, and they will hear it! (Acts 28:26–28)

Some argue Paul's own letters cease to furnish information about his activities long before this time, although others (NIV Study Bibles, for example) date the last source of information being his second letter to Timothy, describing him languishing in a "cold dungeon" and passages indicating he knew that his life was about to come to an end. While Paul's letters to the Ephesians and to Philemon may have been written while he was imprisoned in Rome (the traditional interpretation), they may have been written during his earlier imprisonments at Caesarea, or at Ephesus.

Lacking any biblical reference to Paul's death, we are forced to turn to tradition for the details of his final years. One tradition holds (attested as early as in 1 Clement 5:7, and in the Muratorian fragment) that Paul visited Spain and Great Britain. While this was his intention (Rom 15:22–7), the evidence is inconclusive. Another tradition places his death in Rome. Eusebius of Caesarea states that Paul was beheaded in the reign of the Roman Emperor Nero. This event has been dated either to the year 64, when Rome was devastated by a fire, or a few years later, to 67. An ancient liturgical solemnity of Peter and Paul, celebrated on 29 June, could reflect the day of martyrdom, and many ancient sources articulated the tradition that Peter and Paul died on the same day (and possibly the same year). Chronologically, the tradition that Paul was martyred in Rome is not inconsistent with the suggested mission to Spain. However, there is little additional evidence to support these traditions, though no evidence exists contradicting them either.

It is commonly accepted that Paul died as a martyr in Rome and his body was interred with Saint Peter's in ad Catacumbas by the via Appia where it remained until moved by Lucina and Pope Cornelius into the crypts of Lucina. One Gaius, who wrote during the time of Pope Zephyrinus, mentions Paul's tomb as standing on the Via Ostensis, and the Basilica of Saint Paul Outside the Walls consistently claimed to be built upon Paul's tomb. This claim was given much support by the recent archaeological discovery of a tomb under the basilica bearing Paul's name, the titles "apostle" and "martyr", and dating to antiquity.

According to Bede, in Ecclesiastical History, Paul's relics, including a cross made from his prison chains, were given to Oswy, British King of Northumbria, from the crypts of Lucina by Pope Vitalian in 665.

Writings

Paul wrote a number of letters to Christian churches and individuals, though not all have been preserved; 1 Corinthians 5:9 alludes to a previous letter he sent to the Christians in Corinth that has clearly been lost. Those letters that have survived are part of the New Testament canon, where they appear in order of length, from longest to shortest. A subgroup of these letters, written from captivity, is called the "prison-letters", and tradition states they were written in Rome.

His possible authorship of the anonymous Epistle to the Hebrews had been questioned as early as Origen. Since at least 1750, a number of other letters commonly attributed to Paul have also been suspected by some of having been written by his followers in the 1st century. Source: Wikipedia